You can’t take ’em with you

At Hagerty, we love vintage cars in all their many varieties. Just as there are an infinite variety of collector cars, the experience of owning them is different for everyone. One aspect, however, is universal: When you leave this earth, your cars stay behind.

In that respect, cars are just like all the rest of your stuff. Although one’s car collection may be a small part of the total estate, it’s one that can be especially knotty or problematic. It also can consume more than its share of effort, angst, and expense for loved ones left behind. But with a little bit of fore-planning, that doesn’t have to be so. We of course can’t cover every wrinkle here, and your experience may vary. Rather, think of the following as a basic framework of what to consider and a gentle nudge to begin considering them.

Are your loves their loves?

Some collectors have a spouse, a child, grandchild, or other family member who shares the passion for their vintage car, but more often, none of your heirs feels as strongly about it as you do. Even those who do appreciate and admire your classic car might not feel that they have the knowledge to properly care for it or the space to keep it.

“Everybody knows what to do with inherited money, they don’t know what to do with cars,” says attorney John Draneas, who writes often on collector-car legal issues for Sports Car Market. He adds: “The other thing that is really significant about cars is that they are an asset, and can be a very valuable asset, but they have negative cash flow. They cost money. They may be worth two or three times what you paid for them, but you’re constantly putting money into them: You’ve got to store them, maintain them, repair them, insure them. It takes money to own the cars. So, if you leave them to somebody, whoever you leave them to is going to have to bear the cost of owning them.”

Bearing all this in mind, it’s important to have a frank conversation with your family about whether they would or could become the new steward for your cars or whether they’d likely sell them off.

Make your intentions known

Whatever you decide, make your intentions known. That’s even more important if a car is going to someone outside the immediate family. Have you promised to sell your car to a friend? At a specific price? Make sure those instructions are written down, so that your heirs know your wishes.

“As an appraiser, I’ve actually been witness to this kind of horror story,” says Dave Kinney of USAppraisal in Virginia (Dave is also the Publisher of the the Hagerty Price Guide). “Many years ago, I was hired by an estate to value a 1966 Shelby GT350. It was the deceased husband’s only collector car, and the widow was distraught as her late husband’s ‘friends’ had been getting in touch to ask what was going to happen to the Shelby. One brazen individual actually stated that her husband had supposedly promised the car to him and at a specific price that was severely discounted to the car’s actual value. She was so upset that she was considering a deal at his price.” Kinney suggested that she call her attorney to see if she was under any obligation to sell the car to any specific person or at any specific price.

I now have an ongoing conversation about my cars with my wife, and she knows that nothing is promised to anyone, and if I go before her, she is the one in charge.”

Dave Kinney, publisher, Hagerty Price Guide

“The attorney quickly confirmed that the car was now hers, and she was in control, and as there were no specific instructions, she could do as she wished with the Shelby,” Kinney said. She wound up selling the car to a member of the Shelby Club (SAAC) for a lot more than she was expecting. “That was not an isolated incident,” Kinney says. “The upshot is that I now have an ongoing conversation about my cars with my wife, and she knows that nothing is promised to anyone, and if I go before her, she is the one in charge.”

Making sense of your stuff

If you have a will, then you have named an executor of your estate, usually a close family member. But how knowledgeable are they about your car collection? If the answer is, “not very,” then you can additionally name an executor for specific assets. For example, you could name your oldest son or daughter as the executor of the overall estate but could name a buddy who’s a car enthusiast as a special executor who has authority to deal with the automobiles. Or, you can say that the executor of your estate has to consult with your buddy or with somebody else who’s versed in the ins and outs of owning collectible automobiles regarding the sale of those vehicles. Having someone knowledgeable handling the sale of the vehicles increases the likelihood that your beneficiaries will get the full market value for your cars.

Acting as an executor, however, can be a time-consuming hassle, as those who have done it know. For anyone that you want to act in a representative capacity, it’s important to talk with them now to make sure that they’re willing to tackle the task.

To minimize the burden on whoever is going to settle your affairs, particularly with regards to your vehicles, it helps to stay as organized as possible. First off, make sure there’s someone who knows where all the cars are. Then there are all the spare parts and records such as purchase paperwork, receipts for parts and for restoration work, paperwork for storage rental.

Probate: Avoid it if you can

When someone dies, the assets that they own solely become part of the estate, and they go through a process called probate, after which they’re distributed to the heirs according to the terms of the will. Financial accounts that have named beneficiaries can avoid the probate process, but for collector cars, joint ownership and trusts are the two easiest ways to keep them out of probate.

Why do you want to avoid probate? “[It] can be a pain in the neck because you’re going to have to get a personal representative appointed by the court, you’re going to have to file an inventory of the assets, [and] you’re going to have to file accountings,” says Jeremiah Doyle IV, senior vice president and senior wealth strategist at the Bank of New York Mellon.

Plus, the process can drag out over months or even years. “In my state, Massachusetts, from the date a personal representative is appointed until the date of [assets] distribution, it can be as much as three years,” Doyle adds.

Joint ownership

A collector who has just one or two vintage cars can title the vehicle or vehicles in joint name with their spouse. A car that is jointly titled avoids probate, since the surviving spouse is already a named owner of the vehicle. One important stipulation is that they must title the car in joint name with their spouse with rights of survivorship, as opposed to tenancy in common.

Holding a property as tenancy in common is where two people each have a half interest, and in that case, when one person dies, their half interest is subject to probate. But if a vehicle is owned in joint tenancy with rights of survivorship, when one person dies, by operational law it automatically goes to the joint owner. It does not have to go through probate.

In trusts we trust

Another fairly simple way to avoid the hassles of probate is to set up your own trust that can be revoked, and then transferring the cars into that trust. “That way, the vehicles are no longer in your name, they’re in your name as trustee. That makes a huge difference because now those assets are not subject to probate,” Doyle says, adding: “When you put your cars into a trust, you have to think about the provisions of the trust. Where are those assets going to go? The provisions of the trust have to indicate where that property is going to go if you die.”

While you’re still around, owning vehicles in a trust is not much different from owning them outright. “You have the same rights and responsibilities if you own it in your own name as if you own it in a trust that can be revoked,” Doyle says. On the certificate of title or ownership document, instead of your own name it shows your own name “as trustee.” As the trustee, you still have the power to buy new cars and add them to the trust, borrow against the trust, or sell any cars that are in the trust. When selling a car out of the trust, the bill of sale or transfer document is signed by the trustee as the owner of the vehicle.

Nor does putting your cars into a trust change any income tax owed if a vehicle is sold. “The assets are treated as your own for income-tax purposes, so you pay the tax on the sale,” Doyle notes. And since the trust is revocable, you can tear up the trust any time you want and have the property re-titled in your individual name if you want later on. You also have the right to alter, amend, revoke, or terminate that trust.

Trusts are not complicated to draw up. “You don’t have to go to someone who deals with the Rockefellers to draft a trust,” says Doyle. “Your local lawyer can draft a revocable trust for you. It’s not that difficult.”

Sell now

Some collectors, as they get on in years, begin to wind down their vehicle holdings. The advantage of selling while you’re still around is that you usually have a lot of built-up knowledge about the cars—the history of the vehicles and the specifics of their restoration—that often are lost when the owner passes on.

Still, “few people choose to sell their collection before they die,” observes Eric Minoff, senior specialist at Bonhams. “In part because car enthusiasm is kind of a fatal illness and most people tend to die with it. They don’t want to relinquish the thing that brings them so much joy, even when they may not be able to physically take advantage of using them.”

For cars that have appreciated significantly, there are capital-gains tax considerations that may make it advantageous to pass them on as part of an estate and let the heirs do the selling. If a collector sells a classic car, the difference between the selling price and the price paid (less any restoration costs) is subject to a capital gains tax of 28 percent. So, a collector who wisely purchased a Lamborghini Miura 30 years ago for $100,000 and sells it for $950,000 would owe tax on the $850,000 gain. But if that same Miura passes to through the estate to a fortunate heir of that collector, the heir’s cost basis is not the price paid but is instead the appraised value of the car when he or she inherits it. If the Miura appraises for $950,000, and the heir sells it at auction, they would owe capital gains tax only if the car brought more than that $950,00.

Few people choose to sell their collection before they die….They don’t want to relinquish the thing that brings them so much joy, even when they may not be able to physically take advantage of using them.

Eric Minoff, senior specialist, Bonhams

The cost basis is “stepped-up” from what the deceased collector paid to the appraised value at the time it passes to the heirs. That can be a big factor when a car has appreciated strongly under current ownership. Note, however, that the cost-basis step up is the current law, and is subject to the whims of lawmakers, meaning it potentially could change or go away. And keep in mind that tax law can vary depending where you live.

Arrange now, sell later

There is a middle ground between selling your cars while you’re still around and leaving everything for your heirs to sort out. A collector with significant holdings that are going to be liquidated after his or her passing may want to make arrangements with an auction house or other venue ahead of time to handle the eventual sale.

After all, you’re likely to have a better idea of what cars should be sold at auction and by whom, and which should go to a classic-car dealer, and again which one. As Minoff says, “You as a collector and a hobbyist probably are the one who has relationships with people in the hobby and at auction companies. Unless your children or spouse is as involved in the hobby as you are, they’re starting from square one.”

The process for pre-selecting an auction company to liquidate a collection would look something like this: The auction company would need to familiarize themselves with what is in the collection. They can assist with putting together appraisals. Usually, the cost of the appraisal is only applied if the collection doesn’t come to the company for sale. The collector also negotiates the seller’s commission.

Having the cars sold at the ideal venue maximizes the likely sales price. And making arrangements ahead of time at the very least saves your heirs a major headache. It also can save significant money. “If you have an estate lawyer doing billable hours for all the work in getting pitches from different auction companies or dealers, you’re incurring thousands of dollars of additional costs you could have possibly saved by having made those decisions in advance,” Minoff says.

The tax man cometh

As of this writing, most collectors do not have to worry about their holdings being subject to the estate tax. Under current law, estates valued at $11.7 million or less are not subject to the tax (that figure is doubled if you are married and is indexed to inflation). In 2026, however, the exemption drops back down to $5 million (adjusted for inflation). The exemption figure also could change, as this part of the estate tax is under active review.

A little bit of history is important here. The estate tax exemption has for decades been increasing, and it has gone up a lot. “When I did my first estate tax return in 1977, the exemption was $60,000. That’s it,” says Doyle. “And now it’s $11.7 million. It’s always gone up. I’ve never seen it go down. It went from $60k to $600k, then $625k, then $675k, and then it went to a million, and then they juiced it up to $5 million indexed to inflation, and then they doubled it in 2017 to $10 million indexed for inflation, and that’s where we got the $11.7.”

Those figures all concern the federal estate tax. Some states also levy their own estate tax, and their exemptions can be much lower. The lowest exemption currently is Massachusetts, where the estate tax kicks in at $1 million.

Note also that the $11.7 million dollar estate tax exemption and the gift tax exemption are unified. If all or some of the gift tax exemption is used during lifetime, that subtracts from the amount of estate tax exemption available at death. So, that’s another way the estate tax threshold is, effectively, lower for some taxpayers. Gifts from one spouse to another or estate transfers to a spouse are tax-free, however. They are not subject to the estate tax or to the gift tax.

For estates that are subject to the tax, at either the state or federal level, the assets of the estate—including classic cars—have to be appraised, and the tax is due nine months after the date of death. For those with substantial collections—or other holdings—who will be subject to the estate tax, there are strategies that can be employed. A very small percentage of taxpayers fall into this category, and if you do, you are probably already monitoring your options.

Charitable donation of vehicles

If the heirs are not interested in the collection, a collector might decide to donate their vehicles to a charitable organization rather than sell them. The rules surrounding charitable donations are different for vehicles donated during lifetime versus after death.

If you donate during lifetime, and you want to take an income tax charitable deduction, the rules are complicated. In order to get a federal income-tax deduction for the fair market value of the vehicles, a collector has to 1., hold the cars for more than a year, 2., donate them to a public charity, as opposed to a private foundation, and 3., and most importantly, the donated automobiles have to be put to a use that’s related to the charity’s tax-exempt function. A car museum, for example. That use would be related to their exempt function, and the collector would get a charitable tax deduction for the fair market value of the vehicles.

On the other hand, if the automobiles are donated to a homeless shelter or some other charity where the cars are not related to the organization’s tax-exempt function, the donor can only deduct what he or she paid for the cars (the cost basis). The donor can’t deduct the fair market value of the automobiles.

Donations made to a charitable organization at death will result in a federal estate tax deduction. There is no related-use rule for charitable donations made at death. So, an individual can bequeath a vintage-car collection to any charity and receive a deduction from their estate tax equal to the fair market value of the cars.

If you want the collection to stay together, you can set up your own charity

This is pretty advanced-level stuff, but one way to be certain that your collection is not going to be broken up is to set up your own charity or private operating foundation. You can be on the board of directors of the foundation along with other people, like your kids. That way, you still retain control over the collection.

There are two types of foundations: There’s a private non-operating foundation and a private operating foundation. The difference between the two is crucial. A private non-operating foundation is one where the foundation merely writes checks to other charities. It does not itself engage in any type of charitable activity. If you set up a non-operating charitable foundation, the income-tax deduction is limited to the cost basis of the automobiles, not their fair market value.

An operating foundation is one that actually engages in charitable activity. With classic cars, that would typically be a museum. If it’s a private operating foundation that operates their own charity, the collector can get an income-tax deduction equal to the fair market value of the donated cars.

Note that the private operating foundation can begin during lifetime or it can be part of an estate plan. Again, Jeremiah Doyle explains: “If you wanted to, you could set the private operation foundation up during your lifetime, donate the cars, watch how it works, tweak it. Alternatively, what you could do is have that set up as part of your estate plan so, at death, all these cars that you own are going to dump into the private operating foundation. Maybe your family, your kids, or somebody else who has an interest in the collection runs that operating foundation for however long they want to run it. And you’ll get an estate tax charitable deduction for that.”

As we said, this is advanced-level stuff. Doyle cautions: “The income-tax charitable deduction rules are really complicated. There are a lot of traps for the unwary. A collector really needs somebody that is well versed in collectibles in order to get the right result.”

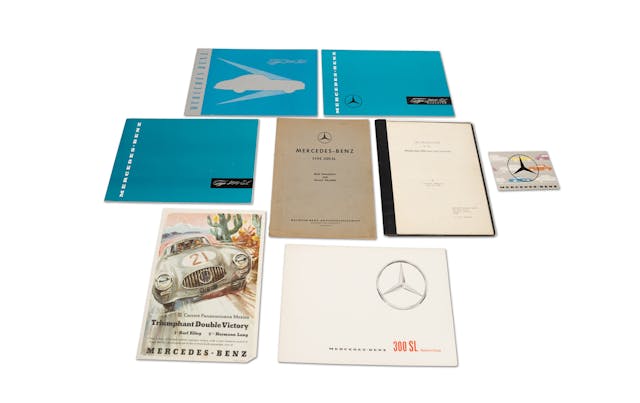

Don’t forget about ancillary materials

For automotive books, literature, and memorabilia that collectors might also possess, the historic value of the items might be significant even if they’re not worth a lot of money. Heirs may not recognize any value of such items, and so you may want to identify organizations such as museums that are dedicated to historic preservation, and earmark certain materials in your collection to them.

Collectors are very attached to [these items], so to imagine them going to the dumpster would be heartbreaking.

Chris Ritter, library director, Antique Automobile Club of America

“We encounter it almost on a weekly basis where a representative of the family will call us and say, ‘My father/mother passed away, and we have no interest in this material. Would you like it?’,” says Chris Ritter, library director for the Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA). The AACA has a library that catalogs sales literature, shop manuals, factory photos, and the like.

The library accepts all donations, although in the event of duplicates, the library only keeps the better copy. “Our eyes definitely light up when we see pre-War sales literature, owner’s handbooks, shop manuals, even original photographs from the ‘50s and earlier are just fascinating,” Ritter says.

“Collectors are very attached to [these items], so to imagine them going to the dumpster would be heartbreaking. That’s why we encourage them to reach out to us and to really think about what they want to have done with them.” While that can be done by the heirs, provided they’d know where to donate, there are advantages for the donor to deal with the organization in advance. “Some people want to make a donation of material, and they don’t want it to ever be split up. We can honor those wishes,” Ritter says. “The items can live on the shelf as ‘The [donor name] Collection’.”

At the AACA library, all items are accessible to the public, not just to AACA members, either on site or through remote research services. The state-of-the-art facility is climate-controlled for temperature and humidity. It also boasts a clean fire-suppression system, so in the event of a fire, there wouldn’t be any damage to materials. As Ritter says, “This is the ideal place for long-term care of paper products. We’ve invested millions of dollars for the future of the hobby and the history. We’re here for the long haul, and we have an endowment to back it up.”

Keep in mind, though, that most cars donated to a museum aren’t likely to become part of the permanent collection. Typically, museums eventually sell off donated cars to raise funds to cover general operating expenses. So, your donated ’55 Chevy might not be displayed in perpetuity for others to appreciate, but the monies raised from its sale will help the museum stick around to serve future generations of enthusiasts.

Planning for the future, even the unpleasant future, is a task for today. Most of us want the best for those who’ll live on once we’re gone, and we may also want the best for the cars we’re so attached to. Take the time now to set things up for a smooth transition for that eventuality. Doing so does not mean you have one foot in the grave; it means you have your eyes focused down the road.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.