Car collectors need to study art history (really)

Leonardo da Vinci lived and worked more than five hundred years ago, but he became da Vinci—arguably the most famous and most valuable artist of all time—thanks to an early 20th-century robbery.

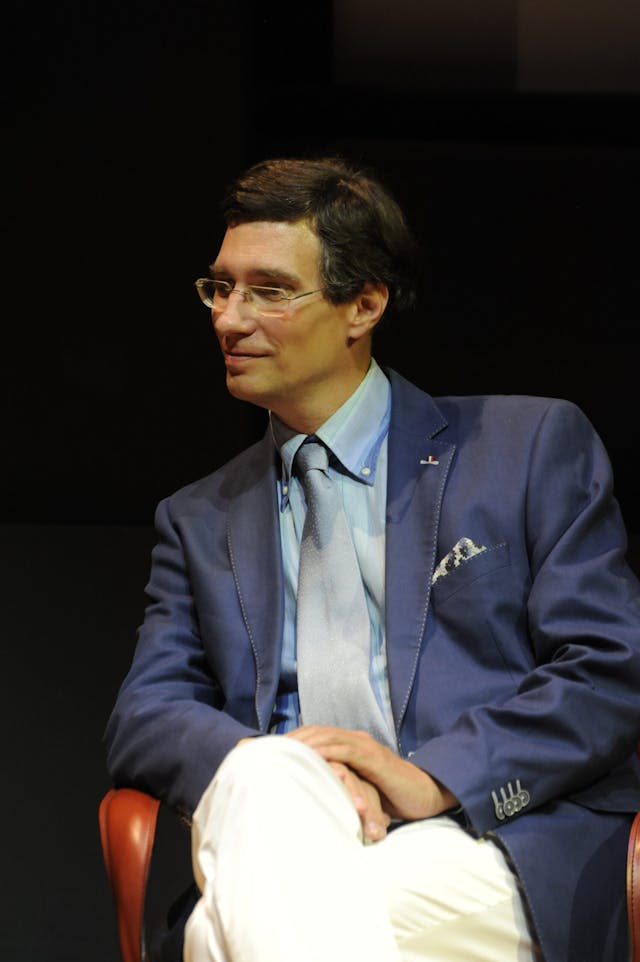

“The Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911. It was the first art theft that really resonated in the mainstream press worldwide, and became the first truly global art market news,” explained Darius Spieth, a professor of art history and art market specialist at Louisiana State University. “Before that, Leonardo was obviously well known and important, but he was one amongst others.”

Some of us at Insider are art enthusiasts; others can’t tell the difference between a Renaissance masterpiece and the stuff hanging in the hallways of the Hilton Garden Inn. But all of us love big datasets. The bigger the sample size, the better we are able to tell you what a car is worth and why. That’s why we constantly dig into Hagerty’s trove of insurance data and why we inspect hundreds of thousands of cars at auction.

The market for fine art is roughly the same size as that for cars in terms of dollars, but it utterly dwarfs us by another metric: time. The automobile is only about 150 years old, and although enthusiasts have been collecting them in some form or another since practically the beginning, the collector car market, as we know it, coalesced only toward the end of the 20th century. In contrast, art has been bought and sold at auction since at least the time of the Roman Empire, and some of companies we recognize today—Sotheby’s, Bonhams, Christie’s—were doing business some 250 years ago.

Spieth focuses on the history of art markets and how technological changes, among other things, have impacted it. We chatted with him about how art markets have (and haven’t) changed over the centuries and, maybe, caught a glimpse at what’s in store for cars over the long run.

We sometimes wonder what will happen to values of older cars as those who remember them new leave the market. What can art history teach us here? Obviously, no one alive today remembers when the Mona Lisa was brand new, and yet it’s still universally viewed as a great work of art.

If you go back in time, to the 18th or 19th centuries, Raphael was king, and Leonardo was a distant second. Today, we put Leonardo first because we’re living in a very technology-driven society. Leonardo did all of these drawings with flying machines, military equipment, and natural sciences, so he resonates much more with our own mentalities. Raphael painted lots of Madonnas and whatnot, and they’re amazing—they’re great—but who gets still excited about that? Taste is an interesting thing.

The list of who is considered famous and great is being reshuffled with time. I’d like to tell a story: There’s a small painting in the Louvre, by an artist called Gerrit Dou, who lived four hundred years ago. The painting is called “The Dropsical Woman.” Napoleon Bonaparte thought this was the greatest painting on the face of the earth. He moved heaven and earth to basically extort it from an Italian nobleman, succeeded, and it’s still in the Louvre. But it’s in the Netherlandish section, and hardly anyone knows the artist any longer. It doesn’t draw the crowds. If this were around 1800, it would be in a bullet-proof glass case and would attract millions of paying visitors every year.

I think every generation renegotiates these things. What constitutes greatness? Consider the change to electric cars. What will that mean if you can no longer have a gas station at every corner? Will that damper the passion for historical cars? I don’t know. Personally, I think it will be the unique craftsmanship that went into classic cars that will be the decisive factor; it will be what defines their endurance as aesthetic objects as well as their role as a storage of value.

That’s interesting. We often talk about how the electrification of the automobile will impact the classic car market from a practical sense—regulations, how we’ll get parts for them, etc. But you’re talking about something different—how electrification will impact desire for classic gas-powered cars.

My thoughts in this discussion always seem to be circling back to issues of psychology. Economists will tell you that humans make rational decisions. I’m not so sure that’s always true. There’s a branch of finance called behavioral finance, which says we need to get away from mechanical models of how markets react to information and keep in mind that we’re dealing with human beings making decisions. Classic cars are a prime example because there are so many psychological—and ultimately irrational—circumstances that define their appreciation; this is what links their market to that of art.

Speaking of finance: To what extent do you think today’s art buyers are actually collectors driven by passion as opposed to investors, looking for financial gain?

That’s a difficult question for me because, to some extent, my gut reaction is to reply from the vantage point of the collector who I am, which makes me biased. On multiple occasions, I’ve paid more than the rational market price for an object. I wanted to have it and I knew this would be the only opportunity in my lifetime. And the segments where I am active is not big-name art. I deliberately buy things that I find interesting, top quality, high craftsmanship, but that are obscure by today’s standards. I could take the same amount of money and invest it in, say, Andy Warhol (or at least prints by Andy Warhol). So, what I’m doing as a private citizen defies the purely rational investment perspective. If you’re really interested in very niche, little-knowns artists, it takes a lot of time to learn about these people—and courage to follow your own convictions. It’s also a major time investment to go down that road, which the busy lives of most people will not permit. So, they go with what the algorithms of a Google search delivers to them—they go for the big names. Real collectors are driven by passion. If you are looking to maximize return on investment, go to the stock markets. Don’t buy art or classic cars.

How important is craftsmanship? Even to a layperson like myself, it’s pretty obvious that certain Renaissance paintings require a tremendous amount of skill, in the same way that someone ignorant of cars probably understands that building a Delahaye or Bugatti required a lot of craftsmanship. But shift to some modern art or, say, a million-dollar muscle car that came off an assembly line and the craftsmanship is harder to see. Does that matter?

If you look at the art world today, “craftsmanship” is almost like an evil word—but not for everyone and not for me; I relish it. But ever since contemporary art came about in the 60s and 70s, the prevailing attitude towards craftsmanship has been, “No, no, no, it’s just about the ideas you have and that’s it. Never mind the execution or whether you know how to draw or paint a human figure.” But in the longer term what matters will be endurance—what people still want to look at, read, or want to own in 30, 50 or 200 years from now.

Interestingly enough, with the advent of computers and the digital age, even our definitions of craftsmanship have changed—especially so in the context of cars. For a long period of time, cars were not seen as “craft objects.” None of them were. But older cars are appreciated from this vantage point today, especially in relation to newer ones. All of the sudden, there’s this awareness that cars, especially from the middle years of the twentieth century, are really these handcrafted objects, they are part of the lure of modernism and the machine age and we need to preserve them because we no longer make them this way. Leonardo made a living as an engineer and many of his drawings are really engineering drawings, so why not look at some of the finest pieces of twentieth-century machinery as art?

What I’m hearing from you is: a lot of what we love and value may be ephemeral. But are there things in the art world that you can point to as more or less permanent?

A while back, I published this book about the art market during the French Revolution of 1789. And one thing that I found quite amazing is that, yes, there are changes over time but not that many after all. There are just some artists who are less known today. But nevertheless, if you look at it over a long period of time, it does not change that much. Auctions, for instance, the quintessential marketplaces for classic cars and art, work in the same way as they worked in the eighteenth century.

If you look at auction catalogs from about 1800, you read long lot descriptions, and wonder, where is this artwork now? What happened to it? And, unfortunately, probably a lot of it got destroyed over time. But then again, it is always surprising just how much is still here.

This whole time we’ve been circling around a very big question: What makes something valuable? And why do we like what we like?

I believe it was Carl Laszlo, a great collector and Holocaust survivor, who said collecting is something that you do in order to overcome your mortality. You want to do something in your life that has a lasting impact. That is what gives purpose. And that has a lot to do with value. And of course, what is value? Ultimately, it is what endures. Even money may lose its value, but assets like land, gold, and art endure. But art still comes out ahead within this group because it has intellectual content. Intellectual content is socially constructed; it is what moves people emotionally. By this point in time, through literature, movies, popular culture, and the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia, this intellectual dimension is something that unites the market for historical automobiles and the art market. The quest for value, and the passion that goes into it, I think you need to have these two things come together.

Let’s talk briefly about NFTs. They’ve taken the art world by storm, and they’ve begun to creep into the car market. What’s your take on them, from the point of view of an art historian? Will they last?

Artworks are basically analog objects, many of them with long histories, because, you know, they have this tactile quality. Look at a painting: It’s a physical thing, you turn it around, and it’s a piece of canvas or a wooden panel with oil paint on it, and you feel connected to the person who did that. It may be crumbling or damaged. No matter how expensive it is, even if you have a $100 million Picasso or whatever, it’s still a piece of cloth with color squeezed out of a tube. The same is true for a $10 painting from the flea market. Right? With NFTs, I think their promoters try to cater to a different, immaterial world, to people with very different mentalities, who consider, like Plato or Kandinsky, the material world a burden.

The NFT marketing machine is piggybacking on the idea of art—they give people the illusion of the prestige that comes with owning original artworks, even cloning the idea of originality. They say, “Oh, here’s your file, but in order to ‘own’ it as something original, you need to pay a huge premium.” The truth of the matter is that the visual image that you get is the same as a JPEG. It’s intangible and infinitely reproducible and exists only on a screen reliant on electricity and software, etc. There are very basic technological constrains on accessibility and the aesthetic nature of the image, which in any case will always be electronically generated (and it shows). So, it’s very much a psychological mind game full of manipulation and self-deceptions. But if that’s what you enjoy, go for it. I doubt that it really appeals to the same people who populate the traditional art, antiques, and classic car worlds. Admittedly, by this point in time, way too much money has been poured into this enterprise, and the hype surrounding it, to pull the plug and say, “Never mind.” It’s going to be around for a while for that reason alone.

Before I let you go, I have to put you on the spot: Do you consider classic cars to be art? If so, where do they fit in the broader art world?

I think there’s a parallel to be drawn between art and classic cars. Believe it or not, I don’t even drive. I don’t own a car. But I love cars, and I appreciate them as both static and moving aesthetic objects.

I’m friends with painter Robert Williams in Los Angeles, who did the original cover art for Guns N’ Roses. He and his wife Suzanne have been part of the hot rod scene for decades, own vintage Ford Model Ts, and turn them into artwork. Of course, they invested a tremendous amount of effort into getting spare parts and going to the meets with other enthusiasts. So, like in the art world, you have the benefit of going to all of these social activities, and then, of course, they go out on the road and drive their cars, getting a lot of attention wherever they show up. So, there’s huge component of social interaction involved in all of that. That’s a much-underrated, added value.

I attended the Venice Biennale in 2022. And if you go to contemporary art events today, you see so many things that are interactive. People want to be engaged in some kind of activity. And that’s also another place where the collector car market overlaps with the art world.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.