“It was a party”: The oral history of the most monumental classic car sale of all time (Part II)

Note: This is the second installment in our series about the Harrah’s collector car auctions—thought by many to be the “big bang” that created the collector car market as we know it today. You can read part I, on William Harrah’s life and death, here. To get a dose of Insider every Sunday, be sure to sign up for the newsletter.

Part II: The auctions

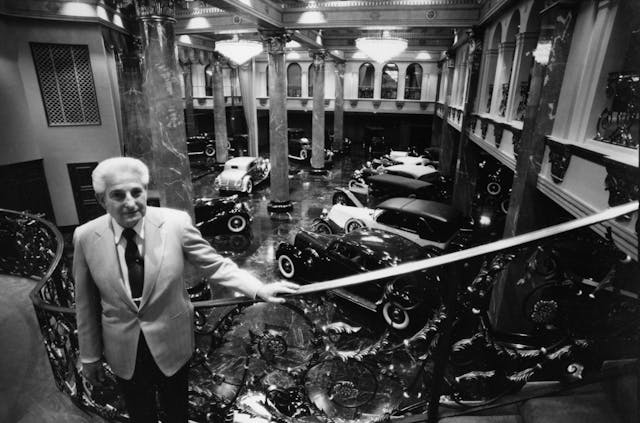

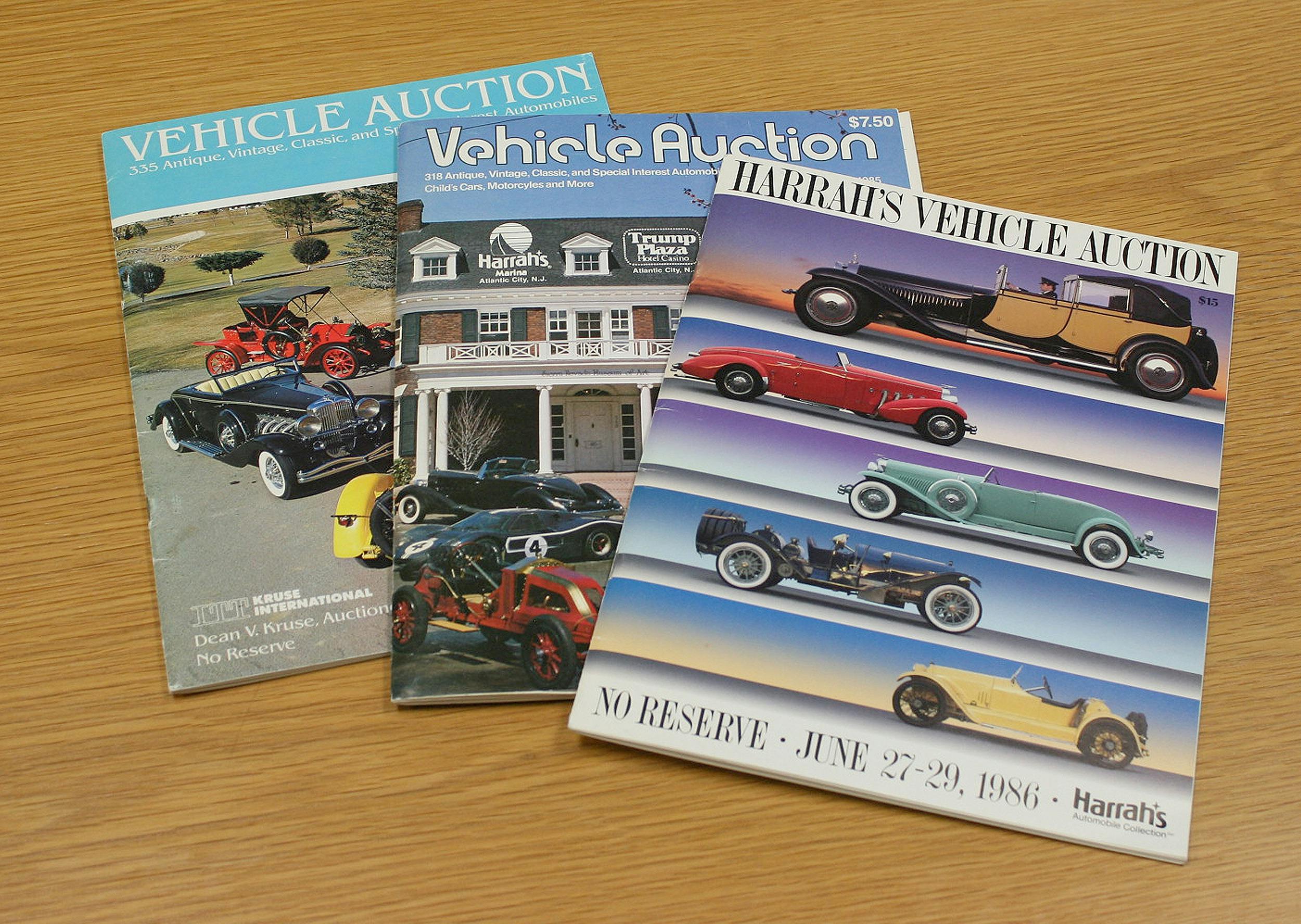

At the end of our last installment, Holiday Inns had purchased the Harrah’s casino empire and, along with it, had come into possession of the late William Harrah’s 1000+ vintage cars. Despite attempts on the part of the state of Nevada and others to save the entire collection, the Holiday Inn board decided to sell the cars at no-reserve auctions (excepting 175 cars and two antique planes that it donated to create the National Automobile Museum, in Reno). Fearing that supply might exceed demand, Holiday Inn split the collection into three sales over three years: September, 1984; September, 1985; and June, 1986. The auctions were held right on the premises of the collection, with well-known auctioneers Don Britt, and Dean and Daniel Kruse running the sales.

“You knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime deal”

David Gooding (CEO of Gooding & Company Auctions): Nobody thought the Harrah cars would ever come up for sale in their lifetime. It was unprecedented. Some of these cars—you never, ever thought you’d have the chance, they’d never be available, they were locked away in a vault. And here they were not only being sold, but sold to the public and at no reserve.

Don Williams (president of the Blackhawk Museum): The word traveled fast … You didn’t need the internet when it came to selling cars like this, and you don’t even need it today.

Charles LeMaitre (classic car collector): People didn’t think these cars would ever come up for sale. And when they did, it was an opportunity for people who know what they were looking at and who understood the value.

Miles Collier (Collector, REVS Institute founder): These were the cars that everybody was desperate for—and here was your shot to get one.

Mark Smith (owner, Smith Automotive Investments): You knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime deal.

“The buzz, the excitement, the crowds.”

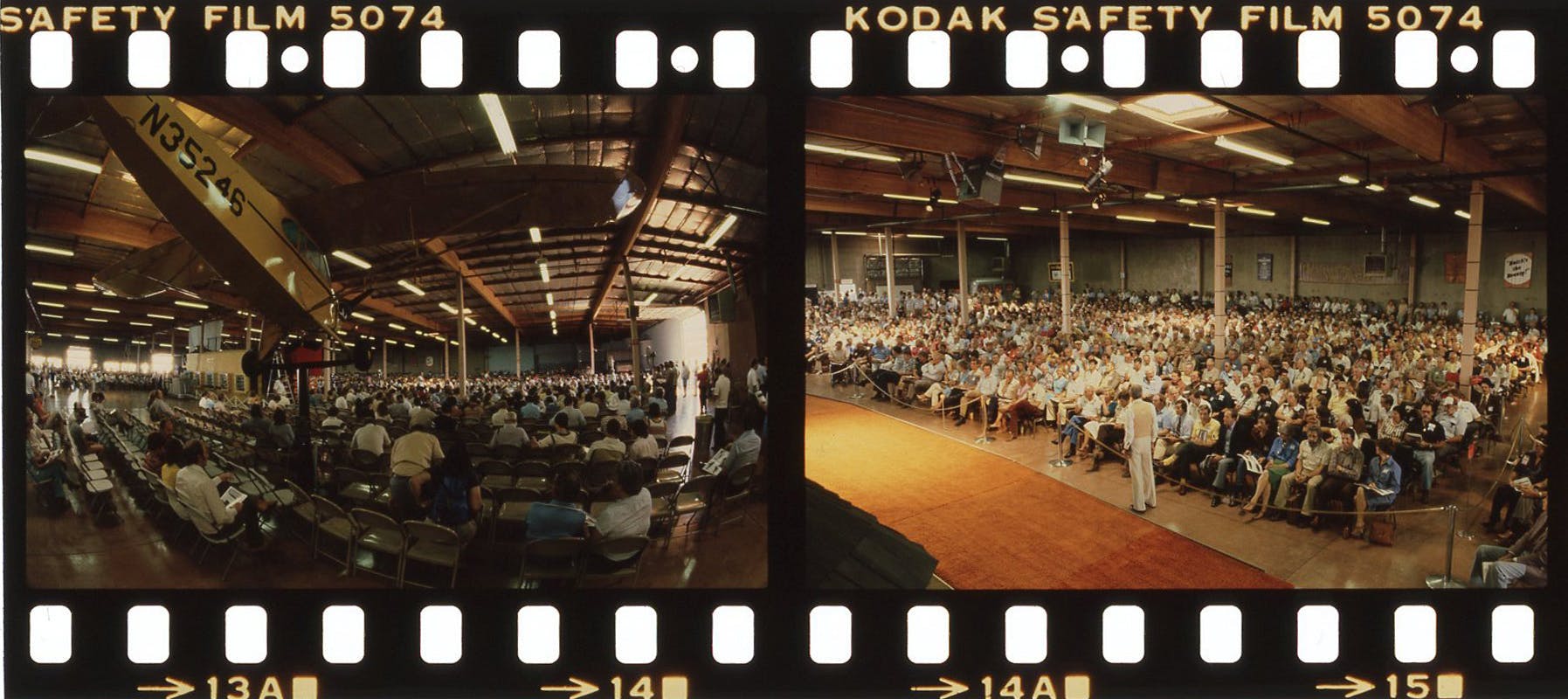

Bruce Meyer (Founding chairman of the Petersen Automotive Museum): The Harrah’s auctions were literally packed with people.

Smith: The overwhelming majority were serious buyers.

Williams: People lined up to come in, to register, had to wait for hours. Nothing on this scale had ever been done.

Gooding: The buzz, the excitement, the crowds, it was standing room only. And in certain showrooms, if you didn’t get there early enough, or didn’t have reserved seats, you had to stand outside the showrooms. You couldn’t even be in the auction.

Meyer: It was a party.

John Mozart (collector): Harrah had had auctions before, where he sold excess parts and cars that they didn’t need, and they always sold everything at no reserve. Being in the gaming business, Bill Harrah’s attitude was, “The market will determine the prices and we’ll see what happens.” Holiday Inn … used that same method. Everything at no reserve.

[The pace was] like a tobacco auction. I would describe it as being somewhere between a classic horse auction and the present day. Don Britt (auctioneer for the first sale) would articulate it clearly—not like Barrett-Jackson where they are rattling off and you can hardly understand what they are saying. He would do it a little bit slower, with clear speech, so you knew when he called the lot.

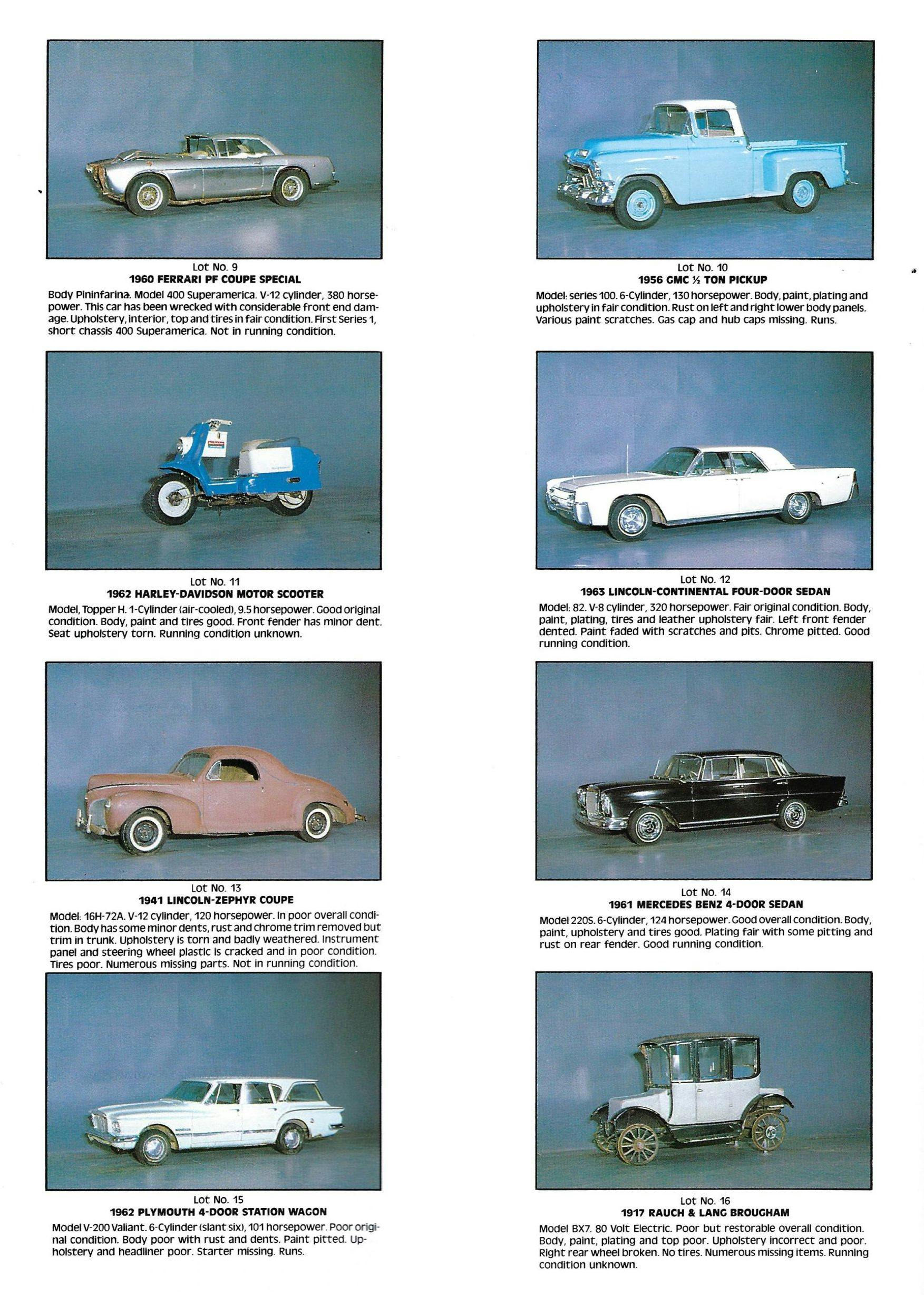

Meyer: They hadn’t really developed any sophistication or décor. It was really just product sold off. There was very little in the way of description in the catalogs. We could look at the cars—it’s been so many years—we knew what we were buying, and we just went after them.

Smith: Compared to today’s catalogs, there were very short descriptions —the photographs were just profile shots, with several cars on a page. A reasonable number of people there were buying cars back that their family had sold, or a friend sold, something they’d always wanted.

Williams: The sales were fast-moving, much faster than today’s sales. Harrah’s auctioneer knew exactly what he was looking at. He also knew the bidders, so he knew where to look to get the bids.

Meyer: Compared to today, the bidding was definitely quicker. It didn’t drag on. You had to know where you were going.

Gooding: Definitely cattle call, but that didn’t dampen the bidding or the confidence in the sale. The fact that it was all no-reserve certainly focused everybody’s attention.

“J.B. just kept taking it to another level.”

Mozart: There were many legendary collectors present, like J.B. Nethercutt, Arturo Keller, Dick Nolan, Don Williams, Jim and Dorothy Conant, and Phil Hill, to name a few. I [also] remember meeting a lot of the dealers from London, who were unheard-of in the U.S. at that time. When they came, they were totally shocked and couldn’t believe something like this could happen. Reno, Nevada, wasn’t a well-established place.

Williams: The audience was like a who’s who of the car hobby.

Smith: J.B. Nethercutt was in full bloom there because he was buying back cars that he had to sell to Bill Harrah when he bought his sister out [for control of Merle Norman Cosmetics].

Clyde Wade (Harrah’s Automobile Collection general manager): When Jack Nethercutt offered his collection of cars, and I think it was around 40 cars, he felt that there was only one guy he knew that could come up with the money right away, and that was Bill Harrah. The issue was Nethercutt needed it the next day, and Bill Harrah didn’t have airplanes back then. Bill got the money (after some challenges with his financial manager), put it in a briefcase, drove all night, and gave Nethercutt his money the next day.

Meyer: [Nethercutt got] the money to buy the cars back, but then Harrah didn’t want to sell them. They were competitors. When they went to Pebble Beach, it was Harrah versus Nethercutt for best of show.

Mozart: A Bonham and Schwartz-bodied Duesenberg J that used to belong to Nethercutt came across the block. I was watching—there were two or three guys with cowboy hats on, sports coats, and nice boots, and they were sitting across the aisle about 10 feet away from J.B. Nethercutt. I used to joke that no one ever said no to him. “No, you can’t have it,” was not in his vocabulary.

Meyer: J.B. was not the kind of guy who would let something go that he wanted.

Mozart: And these guys were bidding on the car, and J.B. just kept taking it to another level. They’d add $25,000 more and J.B. would raise it $50,000. It sold for $1 million, and everybody was shocked. And afterwards, a lot of other important cars brought significant money.

Bill Evans (collector): There was a Stutz Super Bearcat, a fabulous-looking car. I think it was Dean Kruse who was doing the auction, and one guy in the back row was standing up and bidding. And the auctioneer stopped and said, “Sir, you know we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars here?” The guy said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah,” then waved his hat and bought the car. Then he just disappeared. I remember that Clyde Wade was looking for him, and they never found him. They ended up selling the car to someone else.

Collier: The Holiday Inn folks didn’t know anything about cars. They had no idea what they had on their hands—until after the first sale.

Evans: There was just so much stuff. Duesenbergs, Bugattis, 8C Alfa Romeos, great cars like that. But people didn’t understand the truly great cars that were there. A Duesenberg was just a Duesenberg. You look at the differential between the price of a Murphy Roadster versus a Clear Vision or a regular J sedan, there wasn’t a real appreciation of the differences. The “Old Masters” hadn’t been established to the general population yet.

“Jerry Moore wanted to show who had the biggest you-know-whats”

Williams: [Houston shopping-center developer] Jerry Moore was a very active bidder. I’d known him for a long time. He was not as public, and when he bought the [Bugatti Type 41] Royale, he’d had an arrangement with [Domino’s pizza owner] Tom Monahan. They had a prearranged agreement that Jerry would buy the car and sell it to Tom, for exactly what he’d paid for it a year later. He just wanted the publicity.

Meyer: Jerry Moore want to show who had the biggest you-know-whats.

Williams: $6.5 million. The highest price anyone ever paid for a car before that was $1.4 million.

Mozart: I had a business that I’d built up. I sold it a few years before, and I got a really significant price for it, at the time. And yet, I watched this auction and I thought to myself, “If you love these cars, and want to buy some, you’re going to have to make more money.”

“With the money we made on this auction, just think what we can do with the fourth one.”

Wade: After we finished the third auction, I made a comment to my boss, who was a Holiday Inn senior vice president: “With the money we made on this auction, just think what we can do with the fourth one.” All I got was a grin, so that told me the story that there was probably going to be another auction. But they didn’t do it publicly. As it turned out, they started cutting back the personnel at Harrah’s Automobile Collection … so it’d be really difficult to put on an auction. The cost of an auction plus an auctioneer is really high. One buyer came in represented by Ken Gooding [father of David Gooding], who used to be an employee.

David Gooding: They were going to do a final auction in 1987, and they were putting great pressure on Dean Kruse to do that. My dad contacted General Lyon and asked if he wanted to make a run at them.

Williams: General William Lyon was the runner-up bidder on the Royale.

Phil Satre (Former Harrah Corporation president and CEO, currently chairman of Wynn Corporation): [Lyon’s] first overture was that he just wanted to buy the [remaining] two Duesenbergs and the [second] Bugatti Royale. And we said, “We’re not going to do that because we’re still going to have to sell the cars in another auction.” It was … you take everything that we’re not going to donate, or you leave it. He raised his price on New Year’s Eve of 1986. I had to leave my wife at the Harrah’s New Year’s Eve party to go over to the offices and sign the documents at 11:30 p.m.

Gooding: They bought the other Bugatti Royale and 81 other cars, a $28.8 million deal. They were trying to get it on the books before the end of 1986. So, the deal closed; we flew up to Reno with the General. My dad and the General met with the lawyers all day. I was in charge of moving the cars out of Showroom No. 1 into vacant Showroom No. 2. I was in college at the time. I was in charge of blocking out the windows and keeping the press away. It was very exciting.

Collier: General Lyon scooped them all up, and then he sold all the cool stuff. The only thing he wanted was the Duesenberg SJ.

“It’s all a fond memory”

Williams: All the cars brought more than anybody thought they would.

LeMaitre: The cars sold well given the time and the number of cars that were being auctioned that day. In retrospect, I think many of us missed the importance of some of those cars, mainly the classics and the sports cars being offered—and given that the appreciation that has taken place since then, I think it was the opportunity of a lifetime for a serious qualified collector to assemble a great collection of cars, certainly smaller than Bill Harrah assembled. But it was a great opportunity for people who had the vision, who had the means to choose well.

Meyer: Everything looks reasonable now. But my recollection is that they were very fair prices. Because it was a no-reserve auction, everything was getting sold, so the prices weren’t run up. The prices were just what the market would bear.

LeMaitre: It was an opportunity for me, as a young person, to meet serious collectors who I befriended later in my life. So that was very important to me. I’ve made many good friends, as a result of attending those sales. Living back East, it was an opportunity I would never have had.

Williams: It’s all a fond memory, of going there and somehow being a part of it.

Part III, on the legacy of the Harrah’s sales and their impact on the collector car market, will be published next week.

Hey, why don’t you get don williams to tell you the story of how him and richie clyne ripped of Carroll Shelby for CSX2300! It’s a great story!