Putting a value on the Ford GT40

Want a better understanding of what’s driving collector-car values? Sign up for the Hagerty Insider newsletter.

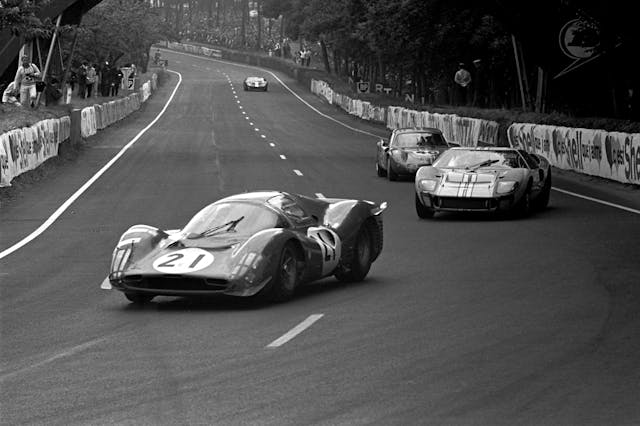

Rivet for rivet, I’m not sure you can find a car that matches the Ford GT40’s raw collectibility. Ford’s mid-engine wunderkind exists at the intersection of historical importance, motorsport legend, iconic personalities, exemplary engineering, and pure desirability. Not every Ferrari race car is important, but I reckon every GT40 built is noteworthy by its existence alone.

Despite that, many Ferraris of similar or lesser provenance trade for millions more. Could it be that the GT40 is undervalued?

Yes, we know there are plenty of zeros involved in the going rate of a finished GT40. It’s not an everyman car, but it is a storybook car, maybe the storybook car in America’s sports car history. That alone is reason enough to seek a better understanding of the GT40’s place into the collector market.

Prancing horse context

If we’re looking at raw numbers, despite all that appeal, it’s usually only a cluster of GT40s with heavy competition history that break the $10 million mark. The rest of the cars—regardless of generation—trade beneath the eight-figure waterline (the “average” GT40 transacts for just under $6 million), presenting a relative bargain compared to some of the superstars from Europe.

Indeed, values of the GT40’s Modenese contemporaries—the 250 LM and the 330/412 P family—have lapped the Ford more than three times over.

The 250 LM has traded in rare air for a long time: public sales dating back to the early-to-mid 2010s saw values as low as $10 million and as high as $17 million. According to Hagerty valuation data, in today’s climate, $17 million fetches a rough 250 LM, while the cleanest attract an average of $24 million.

As for the ultra-rare 330 P bloodline, though modern auction data essentially doesn’t exist—a failed sale in 2009 appears to be last time one crossed the block—we can still provide some context. A source indicated a current owner of a GT40 and a Ferrari 412 P—apparently both purchased long, long ago—regularly fields private offers from interested parties. Of course, the numbers are significant for each, but according to our contact, the 412 P’s offers are up to three times greater than those for the GT40.

Tight supply combined with designs roundly considered some of the most beautiful and well-proportioned cars ever provides enough valuation firepower for these Ferraris to trounce the GT40 almost 60 years after the final checkered flag. But that merely describes the market the GT40 is playing in; it doesn’t explain the fast Ford’s own seemingly stunted values.

Current values

Like most everything in the collector car market, GT40s have enjoyed a solid value run-up in the tumultuous times between January 2019 and April 2023, with the biggest jump seen in October 2022. According to Hagerty data, GT40s in Condition #2 from all generations—ranging from early prototypes to the final Mk. IV “J-Cars” —have jumped some 28%, with the road-focused MK. IIIs and distinctive Mk. IVs showing the largest boost at 35% each.

Compare this to Hagerty’s Blue Chip Index—a stock-market-style index averaging out the values of 25 of the most sought-after collector cars from a wide range of genres—which when set to the same 2019-2023 timeline, is down 2.1 percent.

It seems the market agrees with me; the Ford GT40 is—or was—undervalued, and collectors have taken notice in the last two years. But why did it take so long for this incomparable relic of automotive history to enjoy major appreciation, and what keeps the lid on the GT40’s values compared to European sports cars with less historical significance?

What gives?

According to experts, there isn’t any one factor holding the GT40 back. Instead, several conspire to influence the GT40’s place in the market.

To start, one of the foremost issues is a lack of public sales of great examples. “Most sales are private,” said GT40 owner and expert Johnny Shaughnessy. “They’re harder cars to sell, because like most cars on this level, you need the right buyer.” That means brokered deals—where the sale price isn’t public—rather than auctions carry the day.

Researching GT40s, it quickly becomes apparent the “right buyer” means an “educated buyer,” as there is a dizzying amount of history you need to be familiar with if you’re serious about entering this market. “One of the reasons why the values of the GT40 are held down is because they’re so many series of them, made by so many people, at so many different times,” explains Hagerty Price Guide Publisher Dave Kinney. “It becomes confusing as to what you’re looking at.”

Differences without a distinction

Compared to other dedicated prototype race cars of the era, the GT40 was built in relatively large numbers—and that final production figure is tricky to pin down. If we’re sticking to the original Ford-sanctioned effort between 1964 and 1969 that encompasses the first 12 prototypes through the final run of Mk. IV “J-Cars,” estimates usually peg production around 105 cars.

Within that range, multiple assembly locations and bespoke competition set-ups diffuse those four basic generations into a daunting kaleidoscope of permutations. “There are many differences without a distinction,” says Kinney. “It’s an explanation to anyone outside of the club. With a Cobra, you either have the CSX serial number or you don’t.”

The first cars—Mk. I and assorted prototypes—were developed and built in Slough, UK at the Ford Advanced Vehicles workshop. When the 289-cu-in-powered Mk. I proved mostly unsuccessful, Ford contracted with Kar Kraft to fit the 7.0-liter (427 cu in) big-block V-8 into the Mk. I. Chassis were then shipped to Shelby American and Holman-Moody, Ford’s contracted race teams supporting the program.

Simultaneously, U.K-based Alan Mann Racing continued work on the Mk. I platform at Ford’s behest; five lightweight aluminum-bodied small-block Mk. Is were ordered for Ford’s 1966 Le Mans war party. Two were built before the remaining Alan Mann cars were shifted to the burlier Mk. II platform.

All this variation didn’t stop entirely with the introduction of the road-going-only Mk. III; just seven of these GT40s were built, each finished with subtle production differences and options. Even when Ford brought development almost entirely in-house with the Mk. IV, race cars were almost always seen as a modular canvas to slice, swap, and snip to fit a particular track or race.

Restoration puzzles

Naturally, this diversity makes them one of the more challenging and thus expensive cars to restore. “They are very complicated to restore correctly,” says Shaughnessy. Fresh from a multi-year comprehensive restoration, his 1966 GT40 Mk. I took home a second-place class finish at the 2021 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.

It takes time and the right team to get things just so. “You probably only really have a handful of guys who can do them right. And, two years of my restoration was primarily just research. We ended up digitizing some never-before-seen [GT40] archive photos from Ford, which hadn’t been done before,” Shaughnessy says.

Much of the challenge comes from pinning down those differences in production and preparation, both major and minor. As is the case on most vintage race cars, effective GT40 restorations pick a particular era of the car’s history to return to; meaning, it doesn’t always have to be the car’s first or second phase of use.

Shaughnessy chose to return his Mk. I back to its original street-spec, requiring an inordinate amount of detail-oriented research and planning. He tells me of the herringbone-pattern brake lines he had special ordered and recreated in India, and of $4000 wiper blades, $10,000 headlights, and $16,000 wheels.

Even how the engine was originally dressed is up for interpretation. “They really just used whatever they had on the shelf,” he explains. “Take the exterior finishes on the motor. Some GT40’s blocks were black, others were blue, or heads were blue, heads were black. Cera-coating on the exhaust, no cera-coating on the exhaust. Every car changed.”

In the hot seat

So, you’ve figured out which specific GT40 to get, and persevered through the agonizing restoration process. What’s next?

Well, if you’re like most GT40 owners, you’re probably not going to drive it all that much—especially not on the road. “On the track, they’re fantastic. On the road, not so much,” says Gary Bartlett, longtime enthusiast, collector, and current Mk. III GT40 owner. “They’re small, noisy, and hot. Road tours are maybe not such a great thing.”

Like Shaughnessy’s Mk. I, Bartlett’s GT40 is also a well-restored example—but that doesn’t make it any more friendly to use. Bartlett tells me of his first post-restoration drive, when he and his wife picked up the fresh car from the U.K-based shop, planning on driving it a few hours down a coastal highway to Dover. “It was probably 50 degrees outside, and I thought my wife was going to pass out, it was so hot inside,” remembers Bartlett. “It was brutal. I had to stop to get a water bottle at a gas station, and then turn right around and go back. We didn’t make it to Dover.”

Shaughnessy’s experience isn’t much different. “They’re exhausting cars. You have to deal with greenhouse effect—that’s the biggest problem. That wears you out,” he said. “And, you simply won’t fit in them if you’re six-foot-plus.”

And this is just for 289-powered cars; the big-block 427 Mk. IIs and Mk. IVs are different animals entirely—emphasis on “animal.” Prior to the completed restoration of his Mk. I, Shaughnessy got his GT40 kicks in his 1967 Mk. IV, which, like all Mk. IVs, had the 7.0-liter. “Driving a Mk. IV is tough,” he tells me, quite seriously. “it’s a car you need to approach with a certain level of comfortability and respect.”

Want to race?

Not that you’ll be overwhelmed by events in which to drive your very hot, very cramped toy. Outside of a handful of major classic car rallies, using your GT40 in a vintage racing capacity isn’t that easy, either—at least if you’re in the States. Outside of Monterey Motorsports Reunion, Classic Daytona, and Daytona Historics, and the newly minted Velocity Invitational, there aren’t many opportunities to use your GT40 in a competitive environment in the U.S.

In the U.K. and Europe, it’s a different matter altogether: the vintage racing calendar is packed full, with Le Mans Classic, GT40 classes at Goodwood events, and a GT40-only series hosted intermittently.

Regardless of continent, a not-insignificant amount of owners commission detail-oriented, $500,000 replicas of their real GT40s and leave the genuine article tucked safely in the garage. Free from the constraints of preservation, these replicas can be tweaked for quality-of-life improvements, including seats, cooling, and ease-of-operation.

The real GT40’s road and track usability—or lack thereof—might never have really been part of the equation to begin with. “Most people that own them probably don’t even get them out on the track in the first place,” says Bartlett. “Most just put them in the garage and look at them.”

Who’s buying?

Whether for a fancy showpiece or a Goodwood grid spot, who’s buying the GT40? Superfans of the GT40’s legend and its legacy loom large. Bartlett himself is an indicator: in addition to his Mk. I, he owns an ’05 and a ’19 GT. According to our data, 57% of GT40 owners have at least one 2005–2006 Ford GT in the garage, with an equal amount owning a 2017+ Ford GT. 42% have all three cars in the collection. It seems Ford’s modern GTs are a bit like those replica race cars—a means to enjoy and express the lineage without hurting the real thing, or wearing yourself out.

Age demographics of the three cars aligns with our expectations. GT40 owners are the oldest of the trio at an average age of 65, with the 2005 GT dropping down to 59 years old. As a hot supercar of the moment, the 2017+ Ford GT lops almost decade off the GT40’s demographic, with an average age of 56 for the latest iteration.

Other than devout GT40 enthusiasts, Shaughnessy honed in on Shelby collectors as the primary overlapping demographic, and our data say he’s onto something. 71% of GT40 policy holders with Hagerty also have a Shelby Cobra in their garage, with a further 33% owning an original GT350 as well. The average GT40 owner also appears to be open to other marques, with a surprising 38% owing some variant of the Ferrari 250 GT family. So much for the Ford and Ferrari houses staying divided.

Ultimately, there’s no denying the richness of the GT40’s history or the Herculean efforts Ford and a trove of racing legends put behind honing the GT40 into the weapon it became. Those same efforts challenge restorers today with a mystery of intricate details, and befuddle buyers, who have a harder time discerning what’s “correct.” The driving characteristics and race car sacrifices that added up to victories can be a lot to handle, especially for those not named Miles or McLaren. At the end of the day, GT40 values reflect the overlap of modern realities with a legendary—albeit brief—folio of American motorsport victories on a world stage that remains unmatched.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Hagerty Insider

Deja Vu All Over Again! I’ll take all three.

Well, any “real” GT40 with any history at all is worth millions. And, you could build one for perhaps half a million, and it would be like an original, so why not do that? Since just about every part is reproduced for the racers, this is certainly a way to own a GT40. And if you want to pay millions (for what may be an undervalued car that is going to sit in a collection or occasionally be started to drive on to the show field, go ahead. It’s your money.

Are the values really lagging as opposed to, as you use as an example, a Ferrari 275 LM? There were over 100 GT40s built, maybe more. A handful of the Ferrari LMs, and even fewer of the P3/P4 cars. Is it possible that the GT40 is priced about right? Anyway, I can buy a nice Superformance version in RHD and RH shift, and have about 90% of an authentic car with A/C, for less than 10% of the cost of a “real” one. Maybe the has something to do with the reduced value of a GT40 that is too valuable to drive or race.

BTW, I have driven the A/C equipped SPF GT40 on a hot day and it is not bad at all. ‘Rides well, handles amazingly well with relatively light steering. Speed bumps in parking lots and quiet streets are a challenge, but other than that, it’s actually easier to drive in the canyons that that production Ford GT with the 6″ wide A pillar and wide screen TV sized side mirror. I don’t know how often I might jump into the SPF GT40 for a quick trip to Trader Joe’s for jumbo eggs and milk (it is hard to get out of if the doors can’t be opened all the way), but I would have no problem slicing and dicing the local canyons any weekend morning, or driving the thing to Willow Springs for some lapping.

These are desirable cars that now cost millions (or is it the data plate that is worth millions? That’s another subject, for another time). Discussing how much they are worth is about as relevant as discussing how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. If you want one, be the high bidder.

Curious – Do folks think the Superformance cars with a CSX VIn are worth any more than the ones without?

In 1967 when I was about to order my GT350, a GT40 was in their garage. The ZF transmission was blown so I was not allowed a ride (so they said) BUT, I did sit inside of the RH drive with a RH shifter and, despite banging the back of my head on the clear Plexiglass window shielding me from 8 Webber Fuel Injector tubes I could see my girlfriend’s knees below her mini skirt at eye level! I remember reading an article noting that street GT40s cost $18,000. 3 years later, I bought a new house for $32,412. The GT was a better investment.

I feel all the Ford GTs of all three generations are great investments, especially the generation, 2 2005 06. they are wonderful cars to drive a very simple car to repair and they very seldom have issues. The gen 2s.are still a great investment and Ford has supported them since the early production days and you can still buy most all the parts that you need for the vehicle. I predict that the GEN two GT’s and Gen. three GT‘s will come very close in value over the next few years for a host of reasons. The majority of the new GTs have not been driven. They also limited the sale ability of these vehicles to be held for two years before they’re able to be sold. By my research there is probably only around 2000 GT’s left with lower miles and clean Carfax. Most of these have been driven quite a bit. While the generation three Ford GT’s most have never been driven so eventually there should be an equal amount of high-quality Ford GT‘s Available both in generation two and generation three. The GEN two vehicles Are probably the best out of all three generations produced. For all around use, performance, and comfort.

Please know, I never had the experience to drive to generation one or generation three vehicles I can only make that statement of what I have heard, but I do drive my generation, two Ford on a regular basis, and do have collection of them as well.

The answer is simple for me. Ford outsource the development of their car, whereas the Ferrari is homegrown. For that reason alone I’d pay more for the Ferrari.

Will they take a check?