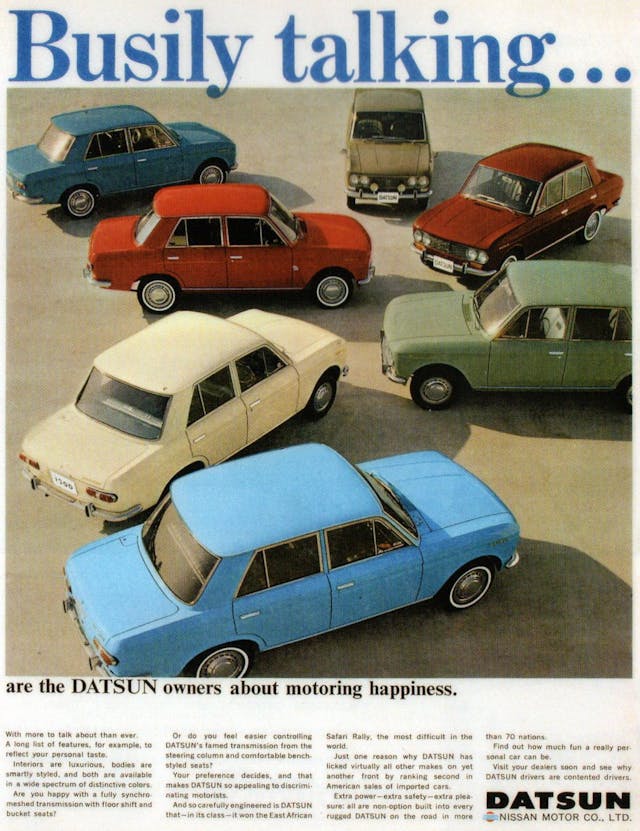

Datsun’s 510 is a fun Japanese classic on the rise

Press a group of enthusiasts to say which Japanese car established a beachhead on American shores and proved that the island nation could build a world-class car, and the Datsun 240Z may well be the only answer you get. It’s no surprise that the Z-car steals the show, but another offering from Datsun, its plucky little 510 sedan, went beyond the sports car world to show the masses that the company could build a fun car for everyone.

On its way to commercial success in the U.S., the 510 built off the work of old-world automakers, benefitted from larger-than-life personalities, and sprinkled some racing victories on top for good measure. As a result, and thanks in no small part to the way they drive, the now-highly-collectible 510s fetch values that belie their economy car origins. That fact may raise some eyebrows, but likely only from those who haven’t gotten behind the wheel of one. Here’s how America fell in love with what affectionately became known as the Dime and why it’s still a beloved classic with Datsun fans in the know.

Learning from Germany

When the first Datsun 240Zs arrived in the U.S. in the fall of 1969, a lot of people were shocked to see a proper sports car from Japan. Datsun fans weren’t, however. For the two years prior to the Z’s debut, while the general public still saw Japanese cars as cheap and disposable, people who had bought the well-priced 510 sedan knew better. Well-built and sporty, the 510 was Japan’s equivalent to BMW’s Neue Klasse.

Though the two companies barely have anything in common today, back in the 1960s Nissan studied Munich’s progress carefully, possibly to the point of copying BMW’s homework. In the postwar period, BMW flailed with bubble cars like the Isetta before releasing the Neue Klasse cars that would come to define the brand in the U.S. When the 1600-2 and later 2002 arrived, they were embraced by the enthusiast press as a light, nimble, and racy alternative to lumbering domestic iron.

Nissan saw a similar opportunity and decided to offer a solution to American consumers who had Oktoberfest dreams but a Budweiser budget. In 1968, for roughly two-thirds of the price of a BMW, you could get a subtle and handsome Japanese sedan that was economical to run and scrappy in the corners. The 510’s recipe was as simple as they come: an affordable, lightweight, rear-wheel-drive family car riding on a fully independent suspension.

Europe in the east

Just as the first-generation Mazda Miata was an everyman copy of the Lotus Elan, the 510 made good on proven themes and technology to become an incredibly popular affordable alternative. Nissan cribbed notes from European automakers Austin and Mercedes-Benz, something made easier by existing relationships and a consolidation-happy domestic auto industry in the 1960s.

Many Japanese automakers built cars under license in the rebuilding period after WWII, and Nissan’s partnership with Austin enabled them to produce direct copies of the Austin A30 and A40 sedan. (If you talk to wily old parts-counter managers from those days, many of them stocked Nissan/Datsun parts for their Austin customers. The Japanese-made parts were identical, but built to much more consistent standards.) Nissan’s work with Austin would provide the stepping stone to its own 410 in 1964. Designed by Pininfarina, the 410 remains attractive, if more than a little overshadowed by the 510 that followed. It originally came with a 60-hp single-carburetor engine, and shared many parts with the contemporary Fairlady (Datsun Roadster). It just needed a little push to achieve greatness.

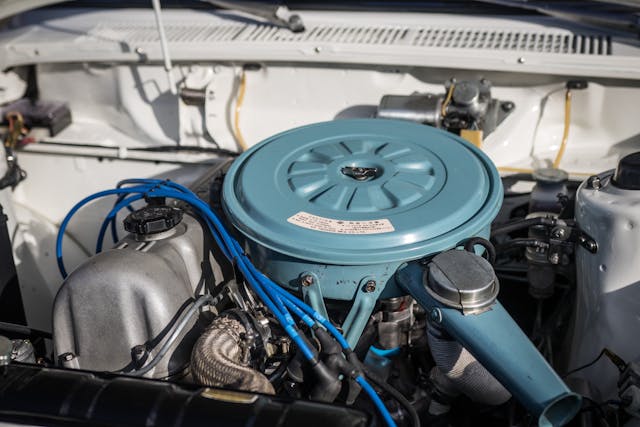

Nissan’s acquisition of the Prince Motor Company took their capabilities a step further. Prince is most famously now associated with the Nissan Skyline’s origin story, but the company brought a wide range of engineering expertise to the table. In the case of the 510, Prince’s engineers had been studying Mercedes-Benz’s four-cylinder engines as benchmarks for durability.

The 2.0-liter four-cylinder that would go on to power Peter Brock’s famous BRE Datsun Roadsters was one such Prince development. Called the U20, it took a Prince Mercedes-inspired single overhead cam head and married it to a 1600-cc Austin-derived block, expanded to 2.0 liters of displacement. For the time, the U20 was a pretty stout performer, rated at as much as 150 hp when fitted with twin Mikuni carburetors and the hottest cam.

While the 510 wouldn’t get this kind of power, some of the lessons Nissan learned in building the U20 would go under the hood of its new economy car. But before that could happen, one of Nissan’s greatest renegades had to resort to some trickery.

The magical Mr. K

Oceans of ink have been spilled about Yutaka Katayama—known by Datsun fans as Mr. K—but not one drop of that ink was wasted. A charismatic and assertive figure, Mr. K frequently found himself at odds with Nissan’s executives. Early on, his obsession with racing as a marketing tool didn’t sit well with top brass. Although his success in a grueling ’round-Australia endurance race in 1958 brought acclaim to the small company, Nissan soon shipped Katayama off to America on what many saw as a fool’s errand to build a dealer network.

Despite a paltry budget, Katayama found success. He first grew Nissan’s U.S. export business with the Datsun brand through small pickup truck sales, but he was forever calling back to Yokohama with demands for a small car. Having slotted right into Southern California car culture like he belonged—he got speeding tickets constantly—Mr. K understood what would and would not sell to Americans. Mr. K didn’t want to push any more toy-like sedans, but instead called for something roomy and light on its feet. Something exactly like the BMW 1600-2, but priced to move.

As plans for the 510 coalesced, it became apparent that being on the end of a phone line didn’t carry the same weight as pounding on a boardroom table yourself. Initially, plans were in place for the 510 to get a 1.3-liter overhead-cam engine, something similarly-sized but more advanced than the pushrod mill found in the 410. Katayama pushed for a 1600 to match the BMW. Headquarters told Mr. K the best they could do was 1.4 liters.

But Katayama wasn’t completely isolated. Sitting on Nissan’s board was Seiichi Matsumura, a new political appointee who had joined from Japan’s international trade organization. Whether because of his familiarity with overseas markets, or the forcefulness of Katayama’s argument, Matsumura agreed to sign his name to a memo written by Mr. K. Everybody knew about the sleight-of-hand, but the board just collectively sighed as the 1.6-liter engine was pushed through for export models.

The 510 was penned in-house by rookie Nissan designer Teruo Uchino. In a pivot from the Italian design cues of the 410 before it, Uchino’s clean, gimmick-free effort helped establish Datsun’s own styling language. It’s aged well, and a 510 can proudly park next to a 2002 of the same vintage.

With Nissan releasing the smaller Sunny sedan around the same time, the 510 moved up in size, growing about five inches compared to the outgoing 410/411. It weighed a little over 2000 pounds depending on body style and trim, had front disc brakes, and featured MacPherson struts up front and trailing arms in the rear for independent suspension at all four corners. (Station wagon versions sported a live axle to handle the additional load.) A four-speed manual transmission was standard, a three-speed automatic optional, and under the hood was the L16 1.6-liter overhead cam engine that Katayama had fought so hard for. It was rated at a peppy 97 hp, but in some markets a factory-installed twin-Hitachi carburetor setup pushed power to nearly 110 hp.

Mr. K’s bet was right. U.S. Datsun sales exploded in the late 1960s, tripling in two years. The 510 cost $1996, slightly less than a dollar per pound. It was about as cheap to purchase and run as a VW Beetle, but roughly twice as fast in a straight line and a delight in the corners. And that was just the factory performance—when the racers got hold of the 510, they really made it dance.

Beating the world

One of the first customers for the Datsun 510 was the late Bob Bondurant, a brilliant racer and instructor who gave racing lessons to everybody from Jeff Gordon to Paul Newman. When he started his racing school in 1968, he first approached Porsche for support. Stuttgart turned Bondurant down, but when he called on Datsun, Mr. K personally said yes. The Bondurant racing school started with two Datsun Roadsters, a 510, a Lola T70 and a Formula Vee.

The 510 proved itself a friendly, predictable, and approachable instruction car. It also put up with a titanic amount of abuse. Everything that made the Dime such a fun little road car translated directly to the track.

Of course, Mr. K also ensured that Datsun would have a racing presence on American tracks. The factory-backed racing teams started with a two-pronged approach in 1971, with John Morton piloting Pete Brock’s California-based BRE entry in Trans-Am racing’s Two-Five class (so-named for engine displacements 2.5 liters and under). From the east, Datsun chose Bob Sharp racing. Right from the get-go, the 510s were competitive.

At that time, BMW and Alfa Romeo held a tight grip on small-bore sedan racing in the States. That all changed with the debut of the 510, however. John Morton won the manufacturer’s championship in 1971, and at the SCCA Runoffs, Bob Sharp finished first. As the 510 kept racking up the trophies, more racers turned to the little Datsun that could, and by the end of the 1970s, the grid was nearly an all-Datsun affair.

The 510’s on-track success did more than bring racers into the fold. Thousands nationwide attended SCCA events during this golden era of sports car racing, and the 510’s prowess translated to sales in the showroom and a strong reputation for cheap thrills on the street. Import tuning culture in the U.S. can trace some of its roots to modified 510s inspired by racers from the ’70s, and that in turn impacts today’s 510 collector market. While other cars from the era might be most valuable in completely factory stock form, a tastefully modified 510 can still fetch solid money.

Stacking dollars for Dimes

The 510’s giant-killer reputation has combined with rust attrition (along with many cars giving up their lives for racing) to drive up prices. Values for the two-door sedan model are the highest, up 85 percent over the past five years to an average condition #2 (Excellent) value of $30,600. The 510 station wagon has skyrocketed as well, posting a 92 percent increase over the last five years and a 24 percent gain in the last year alone. Despite that, it’s still relatively affordable, with an average condition #2 value of $22,100. The four-door trails a bit behind at $20,500, up a little more than 50 percent over five years.

As might be expected, Gen X and younger buyers make up over 78 percent of the market, though that number is nominally down, shrinking two percent over the last three years.

Despite the car’s popularity, 510 public transaction data is a little sparse. While 240Zs roll through the big auction houses regularly, only Bring A Trailer has moved many 510s recently. Several of these have been race cars or heavily modified examples, and they have fetched prices north of $50K—well above condition averages.

That’s quite a lot for what started out as a sort of poor man’s BMW, and in some cases a 510 might fetch more than a BMW 2002. There’s the nostalgia factor, of course, and the racing pedigree, but the 510’s simplicity is also something buyers seek out.

Nissan appears to know this, and in 2013 brought out the IDx concept. The IDx Nismo was a modernized version of the 510’s design essence, powered by a turbocharged 1.6-liter engine making around 200-230 hp, sent to the rear wheels. It would have been a sedan competitor to the Subaru BRZ and Toyota GR86, or, hearkening back to the original, a more affordable rendition of BMW’s 2 Series.

But because there is no more Mr. K at Nissan, we instead got tens of thousands of Nissan Rogues in various configurations. There is still a new Z of course, there to please Nissan enthusiasts. But Datsun fans still know now what they knew then: there are few more fun driving experiences than those found behind the wheel of a Datsun 510.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I have 2 unfinished projects.

Hie I’m looking for a Datsun J15 engine

I just saw one of these this year. First in. Decade.

“Low transaction numbers” because there aren’t many left and people that have them, love them.

These cars have a look/scale unlike anything since that was sold where I live (maybe Euro market has lots…) boxy, compact, athletic with a dash of happy/funny.

I remain optimistic that someday the Nissan IDx concepts return as a real production model, with a normal C pillar, and their proper name: 510.

The Dawson fighting is a memory. When I was a childhood my brother had one is a very nice cars

I own a 1970 521, the truck version of the 510. A 1.8 with dual SU carbs gives it plenty of power.I’ve owned it for 35 years and still enjoy driving it. It was awarded 1st place at the 2003 Datsun National meet at Mt. Shasta. Fewer of these left than 510s so hopefully it’ll increase in value like the 510.